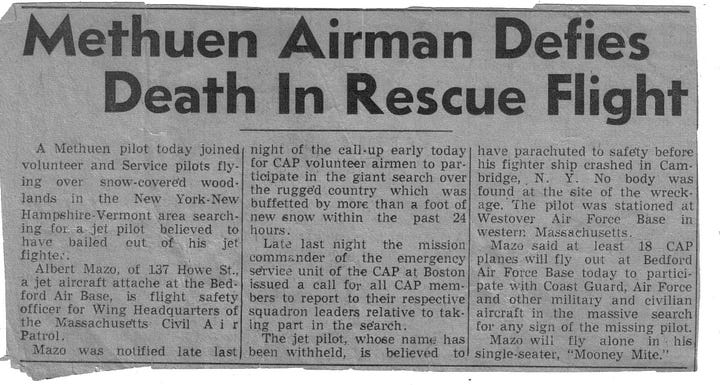

Volume I: The Genealogy of the Imperator; Introduction, Chapter I: A Dynasty is Born & Chapter II: A New American Dynasty

A Tale of Two National Socialists

Introduction

Many who encounter this work will do so without any prior knowledge of me or of the organization known as The New Way. That unfamiliarity is to be expected in a time marked by rapid change, fragmentation, and civic uncertainty. Public life has grown crowded with voices, yet thin in memory; rich in opinion, yet poor in grounding. Before this story can be properly understood, it is therefore necessary that I first introduce myself and establish the voice from which it is told.

This voice is not offered as spectacle, nor as provocation. It is shaped by faith, history, and an abiding belief that nations, like individuals, are accountable to moral foundations that precede them and outlast them. The perspective presented here is informed by the conviction that ordered liberty does not arise spontaneously, but is cultivated—through inheritance, discipline, and a shared understanding of right and wrong rooted in the Christian tradition that has long undergirded our civilization.

What follows is not merely background, but context. It is an account intended to acquaint the reader with the narrator, the origins of this perspective, and the path that led here. It seeks to explain how principles once taken for granted—duty, restraint, stewardship, and continuity—came to be regarded as optional, and why their restoration to public consideration is neither radical nor novel, but prudent.

This work does not presume agreement, nor does it demand allegiance. It asks only for careful attention. In an era inclined toward immediacy, it argues for reflection; in a culture prone to rupture, it appeals to continuity. The purpose is clarity rather than persuasion, and understanding rather than agitation—offered in the belief that a people cannot govern themselves wisely unless they first remember who they are, what they have inherited, and the moral order to which they remain answerable.

My name is Keagan David Mazo. I was born in Haverhill, Massachusetts, on July 9, 1995. As is often the case in an age inclined toward surface judgments, the first point of scrutiny tends to be my name itself.

The given name Keagan is of Gaelic origin, derived from Mac Aodhagáin, meaning “son of Aodhagán,” or more loosely, “descendant of the fiery one,” a reference that traces back to the mythological figure Aed. The historical roots of the name are Irish. I am not. The name was chosen by my mother simply because she found it fitting in sound, not as a declaration of ancestry or identity.

Greater speculation has surrounded my surname, Mazo. Some, applying modern habits of assumption and automated inference, have noted that the name has appeared among jewish families in certain historical contexts and have drawn conclusions accordingly. Such conclusions are unfounded. The surname Mazo is derived from the Spanish word maza, meaning “hammer” or “club,” a term associated with occupation, description, or symbol rather than ethnicity or religion.

Yet I am not Spanish either. My ancestry is, in fact, predominantly Anglo-Saxon and Italian. This raises a reasonable question: if neither Irish nor Spanish heritage defines me, from where does the name Mazo arise? The answer lies not in simplistic categorizations, but in the complex paths of language, migration, and history—paths that this account will examine with care rather than assumption.

The surname Mazzocco belongs to a long-established class of Italian family names, such as my own, formed not from abstraction or status, but from the practical realities of work, place, and daily life. Its origins are linguistic and regional, shaped by the conditions of medieval Italy and preserved through continuity rather than display.

At its root lies the Italian word mazza, meaning a club, mallet, or hammer—a common implement in agricultural, forestry, and craft labor. The term descends from Late Latin (mattea / mateola) and entered the vernacular well before surnames became hereditary. In this context, the name emerged not as a symbol, but as an identifier readily understood within local communities.

Emidio De Felice, the leading authority on Italian surnames, places names derived from mazza squarely within this tradition of practical identification:

“I cognomi derivati da mazza sono per lo più soprannomi o nomi di mestiere.”

Translation: Surnames derived from “mazza” are for the most part nicknames or occupational names.

— Emidio De Felice, Dizionario dei cognomi italiani (Mondadori, 1978)1

The form Mazzocco is further shaped by its suffix. The ending -occo is a descriptive and regional element, characteristic of popular speech in central and southern Italy. It functions to emphasize association or familiarity, reinforcing the practical character of the name rather than elevating it into symbolism.

As linguist Carla Marcato notes in her study of Italian onomastics:

“Suffissi come -occo appartengono alla formazione popolare dei soprannomi, con valore descrittivo o rafforzativo.”

Translation: Suffixes such as “-occo” belong to popular nickname formation, with descriptive or intensifying value.

— Carla Marcato, Nomi di persona, nomi di luogo (Il Mulino)2

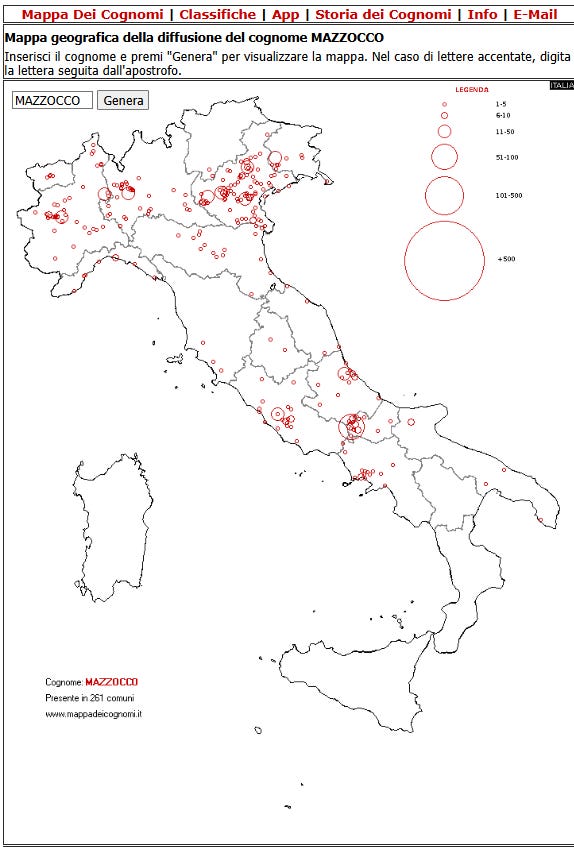

In regions such as Molise, where settlement patterns remained stable and migration limited well into the modern period, surnames like Mazzocco became fixed later than in major urban centers and remained closely tied to locality. This regional persistence is not incidental; it reflects the enduring social structures of rural Italy, where families, trades, and names were bound to specific landscapes across generations.

Michele Francipane observes this pattern in his survey of Italian surnames:

“Nelle aree rurali dell’Italia centro-meridionale i cognomi si fissano tardi e restano legati al territorio.”

Translation: In rural areas of central-southern Italy, surnames became fixed later and remained tied to their territory.

— Michele Francipane, Dizionario ragionato dei cognomi italiani3

The social character of the surname follows accordingly. Names of this type belonged not to courts or titles, but to craftsmen, laborers, and rural households—families whose continuity was measured in years of work rather than in records of rank. De Felice is explicit in distinguishing such surnames from aristocratic formations:

“I cognomi di mestiere e soprannome appartengono agli strati popolari della società medievale.”

Translation: Occupational and nickname surnames belong to the popular strata of medieval society.

— De Felice, Dizionario dei cognomi italiani4

When bearers of the name later emigrated, particularly during the great Italian diaspora of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the surname was often shortened or modified in official records. This process did not alter its origin, but it did obscure it.

Joseph G. Fucilla documents this phenomenon in his study of Italian surnames abroad:

“Italian surnames were often shortened or modified in immigration records.”

— Joseph G. Fucilla, Our Italian Surnames (Genealogical Publishing Company)5

Taken together, the historical record presents Mazzocco as a name formed through use, fixed through locality, and carried forward through continuity. It is neither emblematic nor ideological. It is descriptive, regional, and rooted in labor—reflecting a lineage shaped by function, endurance, and place rather than abstraction or status.

Of all the accessible books that you could search for, the surname Mazzocco is referenced only once by a jew. It is listed in A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from Italy, France, and “Portuguese” Communities (2019) by Alex Beider, but there are no specific mentions of a person or a family that use Mazzocco as a surname and there is no mention of which region where the surname was used by jews. It should also be noted that no other academic source includes the surname Mazzocco as a surname used by jews. It is most likely that Beider is referring to a potential case in one of the high population centers in Northern Italy.

For further proof that my family is not of jewish origin, there is the fact that there was never any documented case of jews in Cerro al Volturno. This is especially important because the Italian Fascists set up an interment camp in nearby Campobasso, yet they did not document any jews being arrested and interned in that camp from Cerro al Volturno.6

Mappa geografica della diffusione del cognome MAZZOCCO

A Dynasty is Born

Since our last name was first set down in record, there was a member of my family living within the stone walls of the fortress town of Cerro al Volturno, in the high country of Molise, Italy. There, generation after generation labored the earth, cut stone, raised walls, and gave their strength to works meant to endure beyond a single lifetime. What they built still stands, weathered but unbroken, bearing the quiet mark of hands long since returned to the soil. To this day it is my family that controls that fortress on the hill.

Cerro al Volturno itself reaches back to antiquity. It was first founded in the third century before Christ by the Samnites, a people forged by war and mountain life, who understood defense, endurance, and loyalty to land. Long before Rome ruled these hills, my ancestors stood watch over the valley, and long after empires rose and fell, families like mine remained—bound not by titles, but by duty and place.

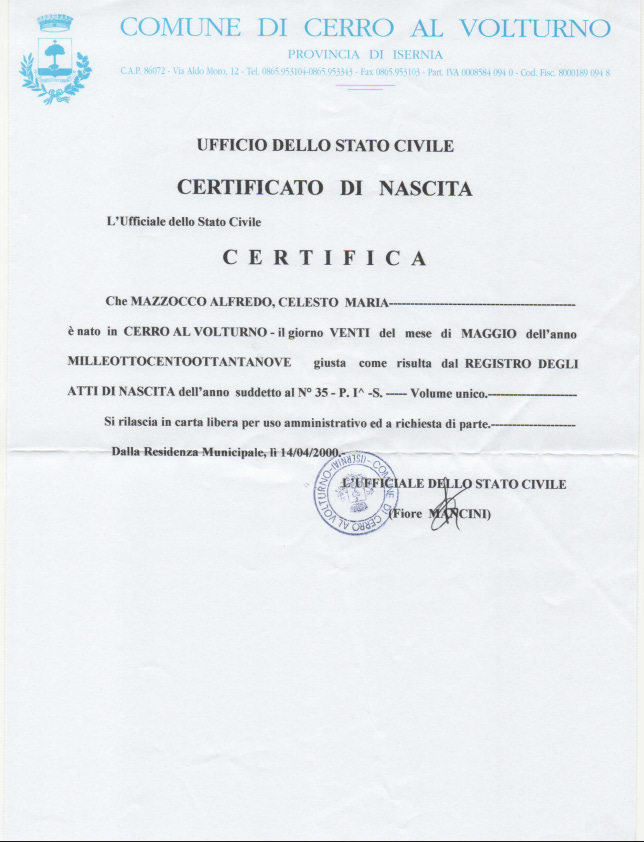

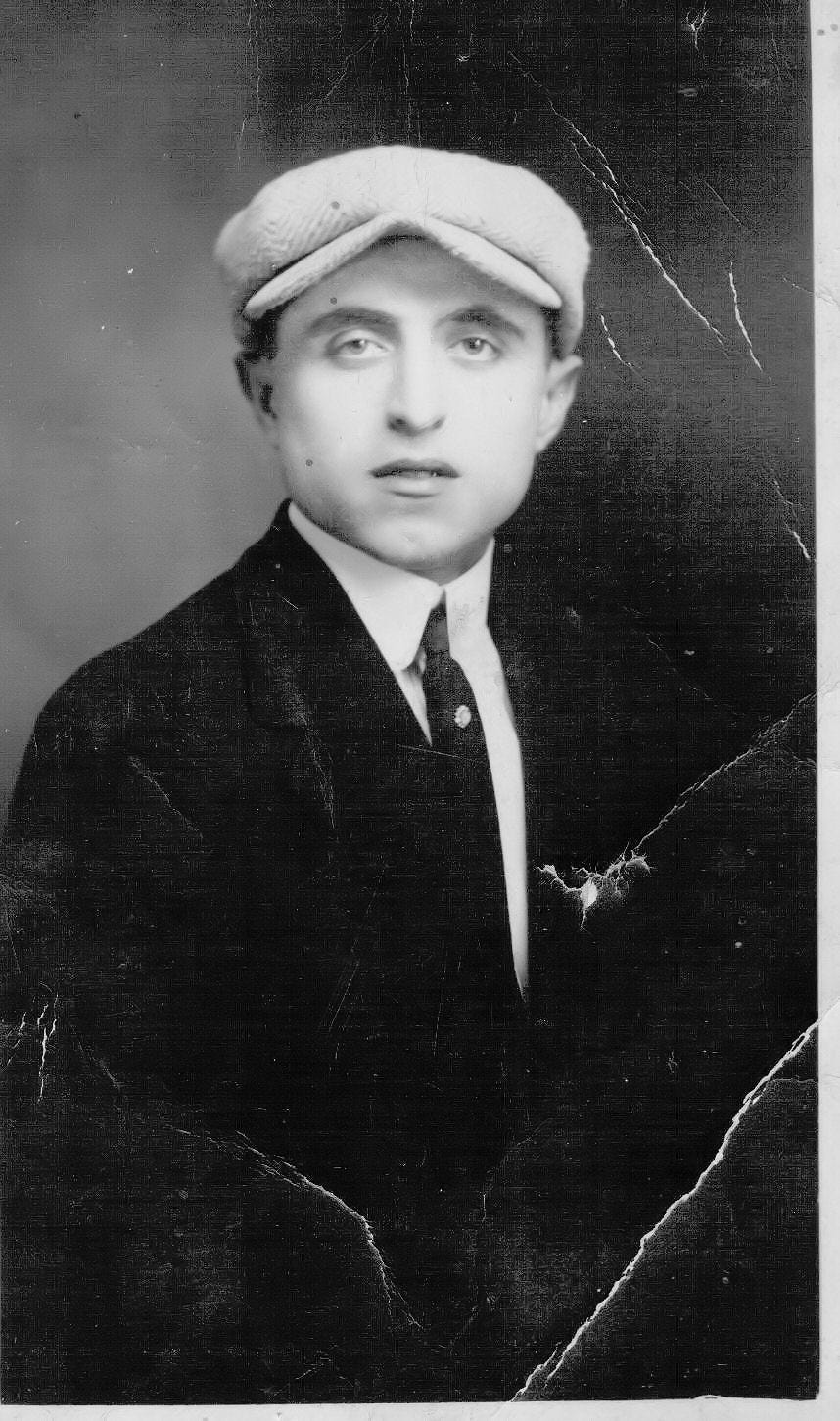

By the closing years of the nineteenth century, the rhythms of life in the fortress had changed little. Birth, labor, and death followed ancient patterns. It was customary for pregnant women to travel down from the mountain to give birth in the city, where physicians and midwives could be found, before returning home with their children once strength had returned. Thus, in 1889 anno Domini, my great-grandfather Alfredo Alberindo Celesto Maria Mazzocco was born in nearby Campobasso, the capital of Molise, his blue eyes opening first to a world already shaped by stone, labor, and obligation.

From his earliest days, Alfredo belonged to two worlds: the ancient stronghold of his ancestors and the widening horizon of a changing Italy. His blue eyes marked him as different even among his own, yet he was no less bound to the land or its demands. By the grace of God, he was given a mind for the mechanical, an uncommon gift in a place where survival depended more on muscle than on design. He learned to understand tools, movement, and structure—not only how things were built, but why they worked. Poverty pressed heavily on the countryside, opportunity grew scarce, and the old ways—though honorable—could no longer promise survival. What had sustained families for centuries now demanded a sacrifice of its own.

So it was destined that Alfredo would leave. In 1906, carrying little more than his name, his faith, the memory of stone walls older than nations, and eyes that had learned to look beyond the valley, he set out for the New World. He left behind the fortress town that had shaped his bloodline, crossing an ocean not as an adventurer, but as a laborer—one link in an unbroken chain, carrying the weight of the past forward into an uncertain future.

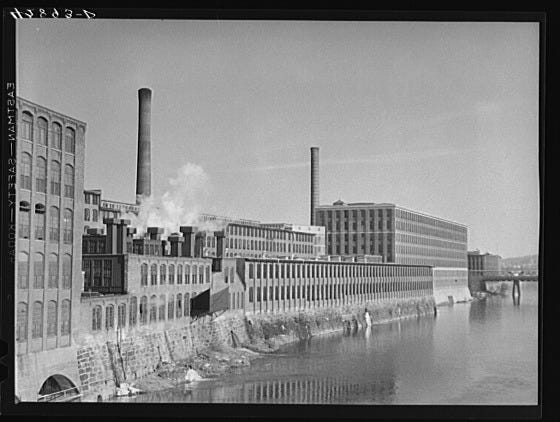

When my ancestor crossed the ocean in 1906 at the age of 17, he carried with him a name shaped by centuries of use in the stone towns of Molise. But in Lawrence, Massachusetts, names were often shortened, altered, or simply replaced—reshaped to fit mill ledgers, pay envelopes, and English tongues. It was there, within the industrial order of the city, that Alfredo Mazzocco became known as Alfred Mazo.

The change was not ceremonial. It required no consent, only repetition. Foremen wrote what they could pronounce. Clerks recorded what fit the line. Over time, the abbreviated name became fixed in employment records, housing documents, and daily speech. What had once been a full inheritance was reduced to something more manageable, though not less real.

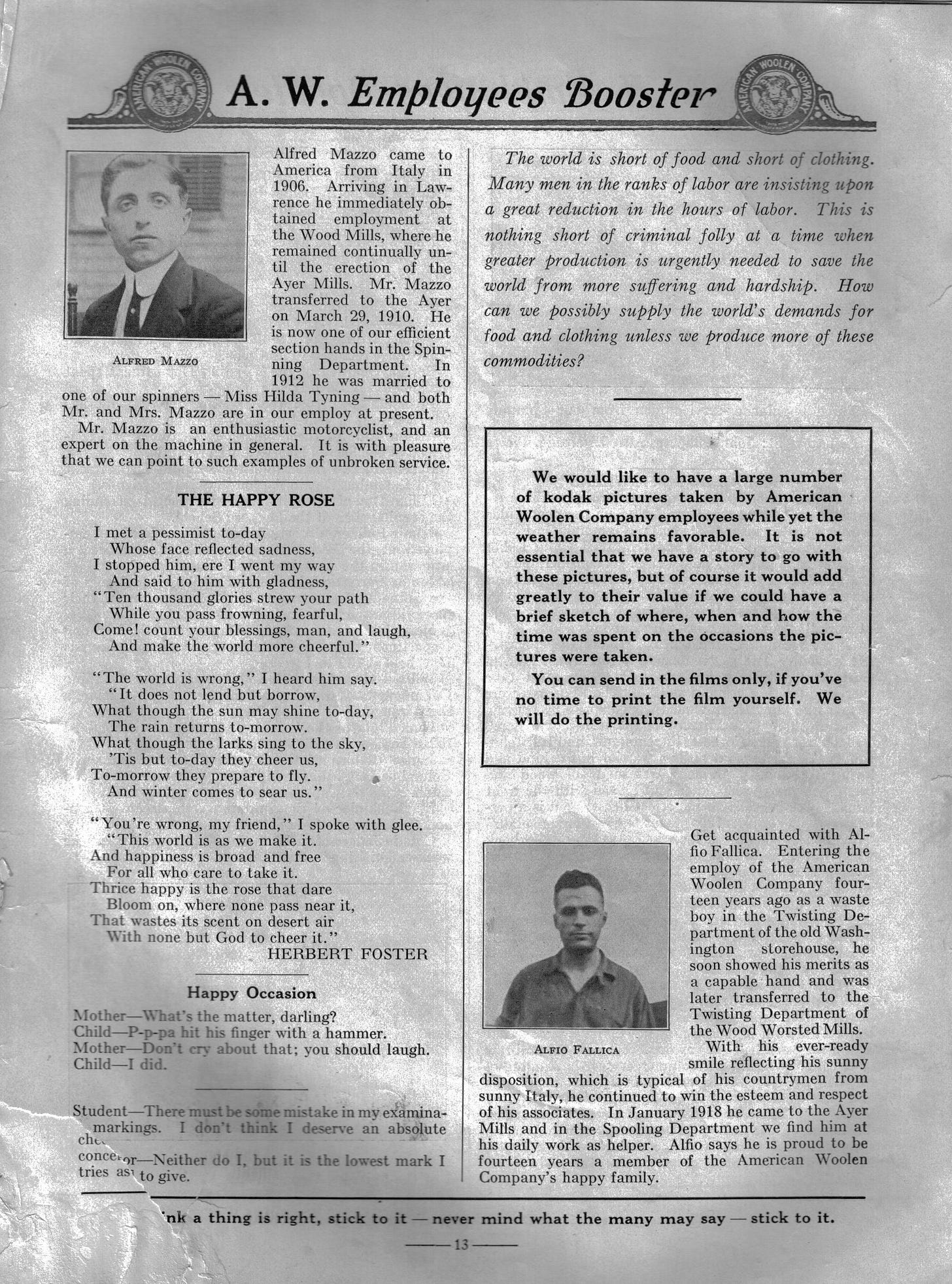

Under this new name, Alfred Mazo worked in the Wood Mills, laboring long hours amid the noise, dust, and danger of the textile floor. The work did not distinguish between names old or new. Strength, discipline, and endurance mattered more than origin. Inside the mill, identity was measured by output and obedience to the bell.

It was there that his gift found its purpose. Alfred understood the machines not as obstacles, but as systems. He learned their rhythms, sensed their failures before they came, and kept them moving when others could not. While many labored only with their bodies, he labored also with his mind, maintaining, adjusting, and coaxing order from iron and motion. The same discipline once used to raise stone walls in Molise now kept the looms of Lawrence alive.

The Wood Mills demanded the same qualities his family had long practiced: endurance, precision, and silence. The work was relentless. Days stretched ten to twelve hours, six days a week, measured by the whistle and the turning of belts overhead. Wool dust filled the air, settling into lungs and clothing alike. Machines did not pause for fatigue, and injury was an accepted risk of survival.

Outside the mill, the old name endured quietly. Among fellow Italians—men who shared dialect, memory, and loss—he remained Alfredo. Letters sent back to Molise bore the name his parents gave him. The fortress town still knew who he was, even if America did not.

The renaming marked a crossing as real as the ocean itself. It was the moment when the old world yielded to the demands of the new, not by force, but by necessity. Yet the substance of the man remained unchanged. What had been forged in stone in Cerro al Volturno could not be erased by ink.

Thus the line continued in America under a shortened name, but with the same blood and obligation. Alfred Mazo carried forward what Alfredo Mazzocco had inherited—endurance, faith, and the memory of walls older than nations—into a country that would never know the full weight of what it had renamed.

And outside the mill, life was narrow but ordered. Alfredo lived in a crowded tenement with other Italian laborers—many from Molise and neighboring regions—men bound by shared dialects and memory of stone villages left behind. Meals were simple, often taken late and without ceremony. Sleep was brief and necessary, not indulgent.

The Italian community in Lawrence provided what the mills did not. Churches, mutual-aid societies, and informal family networks replaced the protections once offered by the walls of Cerro al Volturno. Letters traveled back across the Atlantic, carrying news home whenever time could be spared. The old world was not abandoned; it was sustained at a distance.

Alfredo carried with him skills and habits formed long before America—knowledge of hard labor, restraint, and obligation. Where his ancestors had raised and maintained fortress walls meant to withstand centuries, he now fed machines designed for endless production, indifferent to the men who served them. Yet the discipline was the same.

Lawrence in 1906 was already strained beneath the surface. Wages were low, accidents common, and resentment quietly growing. The great strike that would later make the city infamous had not yet come, but its causes surrounded him daily within the Wood Mills’ brick walls.

It was here, amid the noise and smoke, that the line continued. Alfredo did not build stone fortresses in America, but he preserved something older—an inheritance of endurance and faith—carried forward into a new land, where the name would take root once more.

He remained at the Wood Mills through the closing years of its operation, giving his labor and skill to the looms until a turning point arrived in 1910. On March 29th of that year, the erection of the Ayer Mills marked a new chapter in Lawrence’s industrial life. With the rise of this larger and more modern complex, the center of work shifted, and with it the paths of the men who kept the machinery alive. Alfred stood at the threshold of this change, shaped by years among belts and gears, prepared by experience to move forward as industry itself advanced.

With time and experience, he became an efficient section hand in the spinning department, trusted with the steady operation and maintenance of the machines that governed the pace of the mill. His mechanical mind, shaped by years of observation and discipline, found its place among the frames and spindles, where precision mattered as much as endurance.

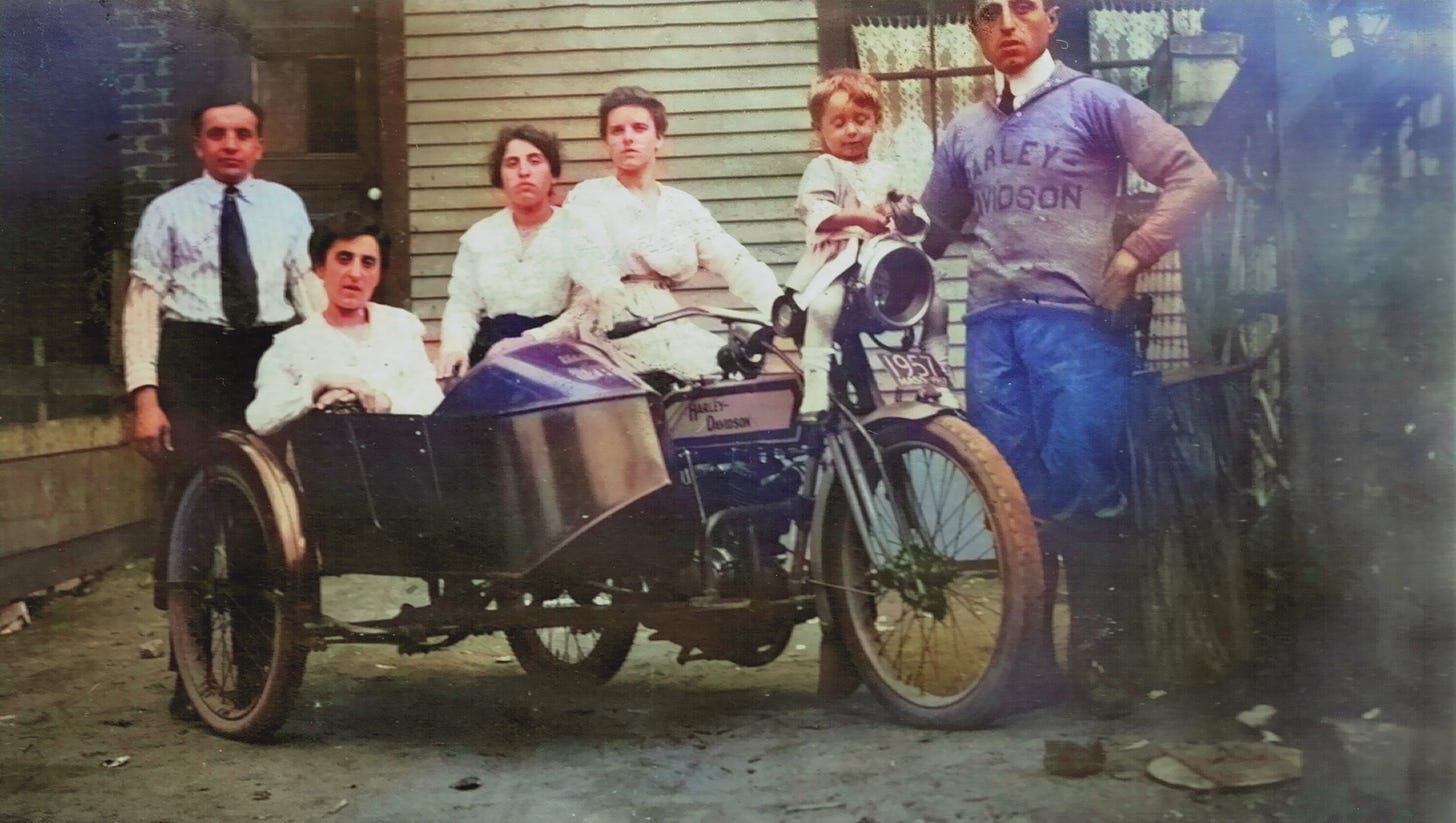

In 1912, his life in Lawrence took on a deeper permanence. He married Hilda May Tyning, herself a spinner in the mill, a woman who understood the same long hours, the same noise and dust, and the same quiet resolve demanded by the work. Their union was forged not in comfort, but in shared labor and mutual understanding.

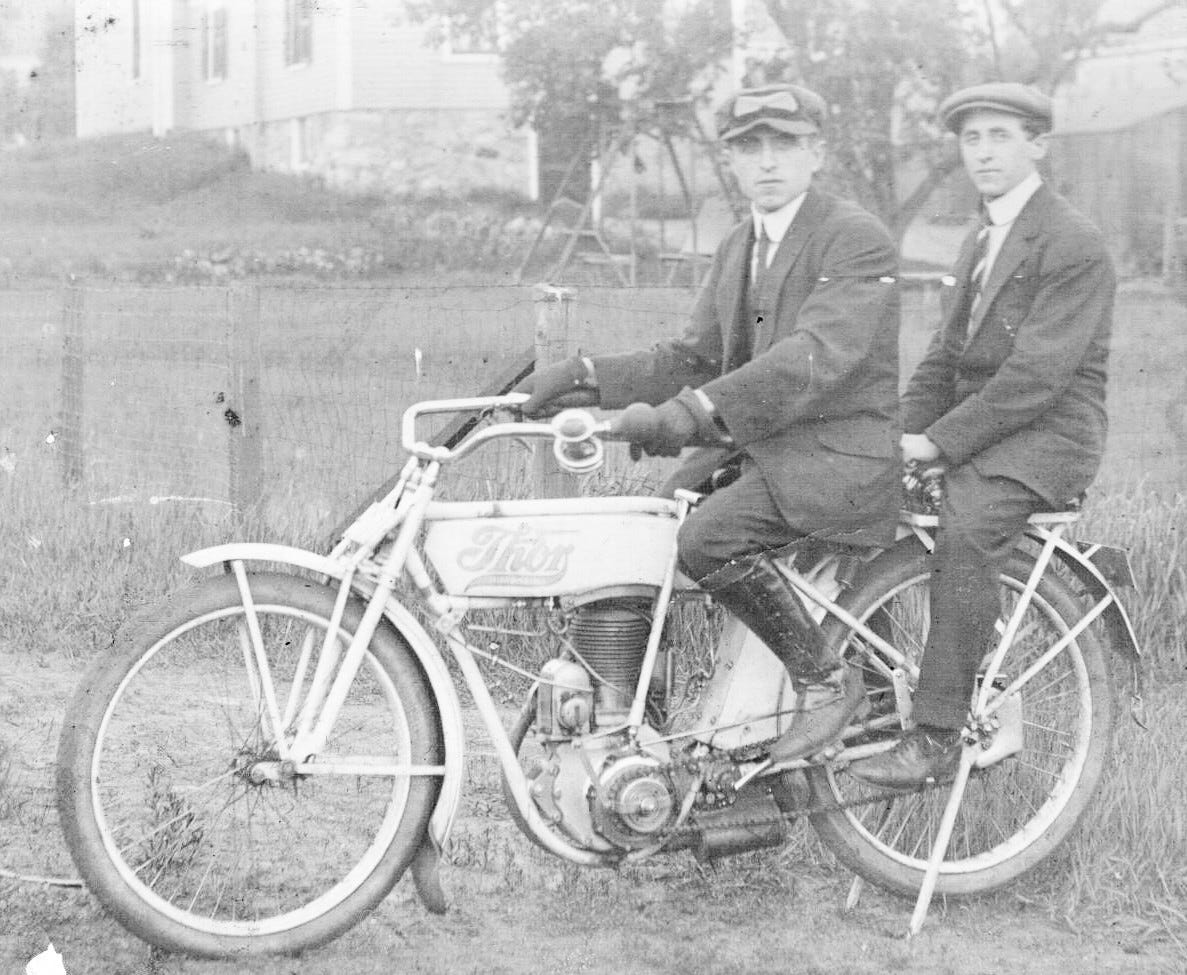

When he was not tending the mill’s machinery, he turned his attention elsewhere. Drawn to motion and mechanics beyond the factory floor, he became an avid motorcyclist. Where the mill bound him to schedules and walls, the motorcycle offered movement, independence, and speed—a modern expression of the same instinct that once drove him across an ocean. In engines and open roads, he found both mastery and release, a balance between duty and freedom that defined his life in the new world.

A New American Dynasty

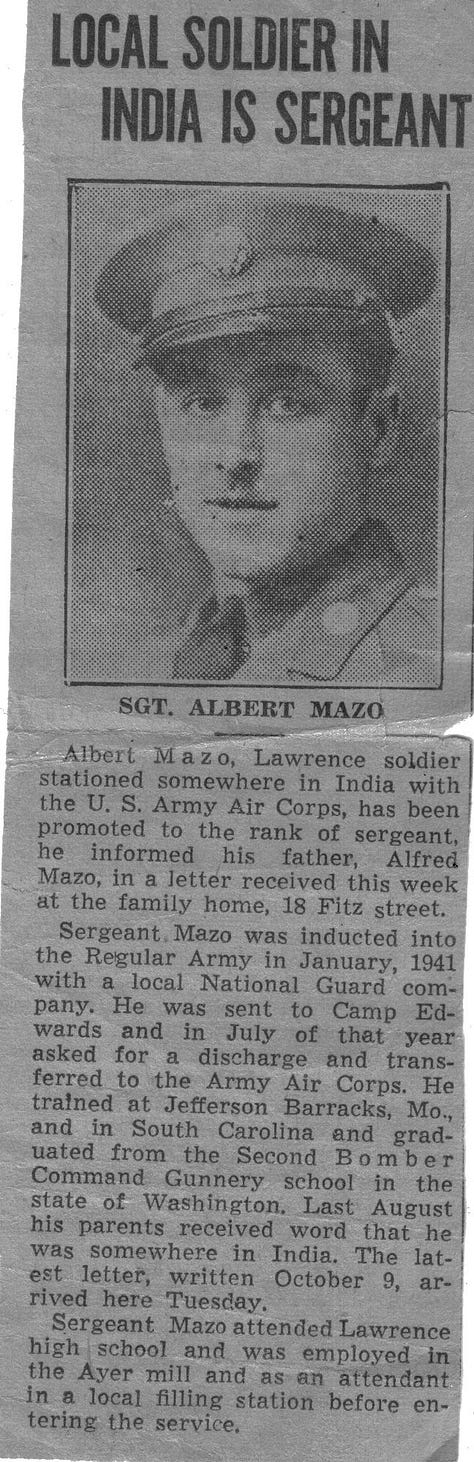

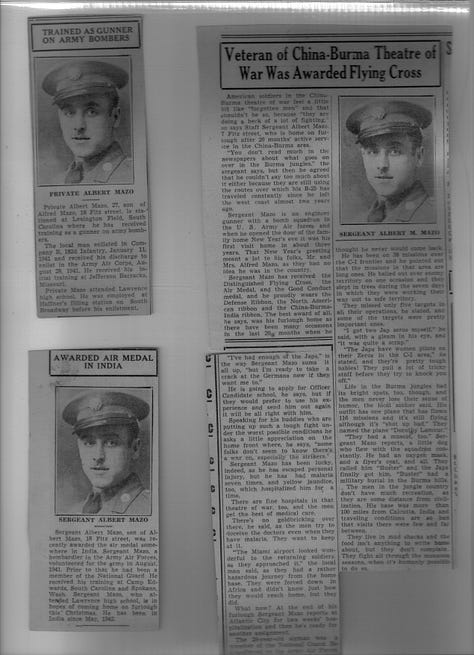

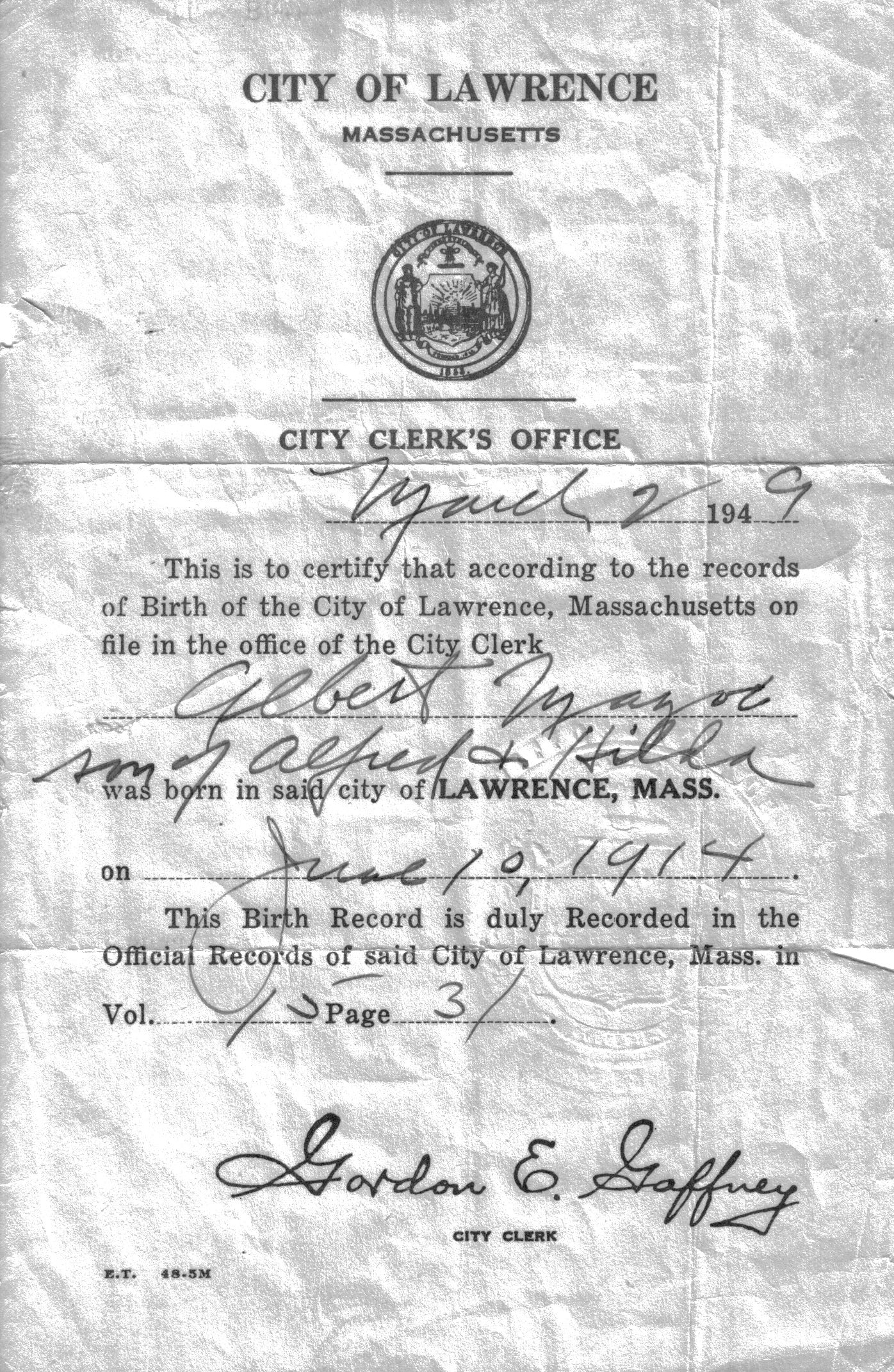

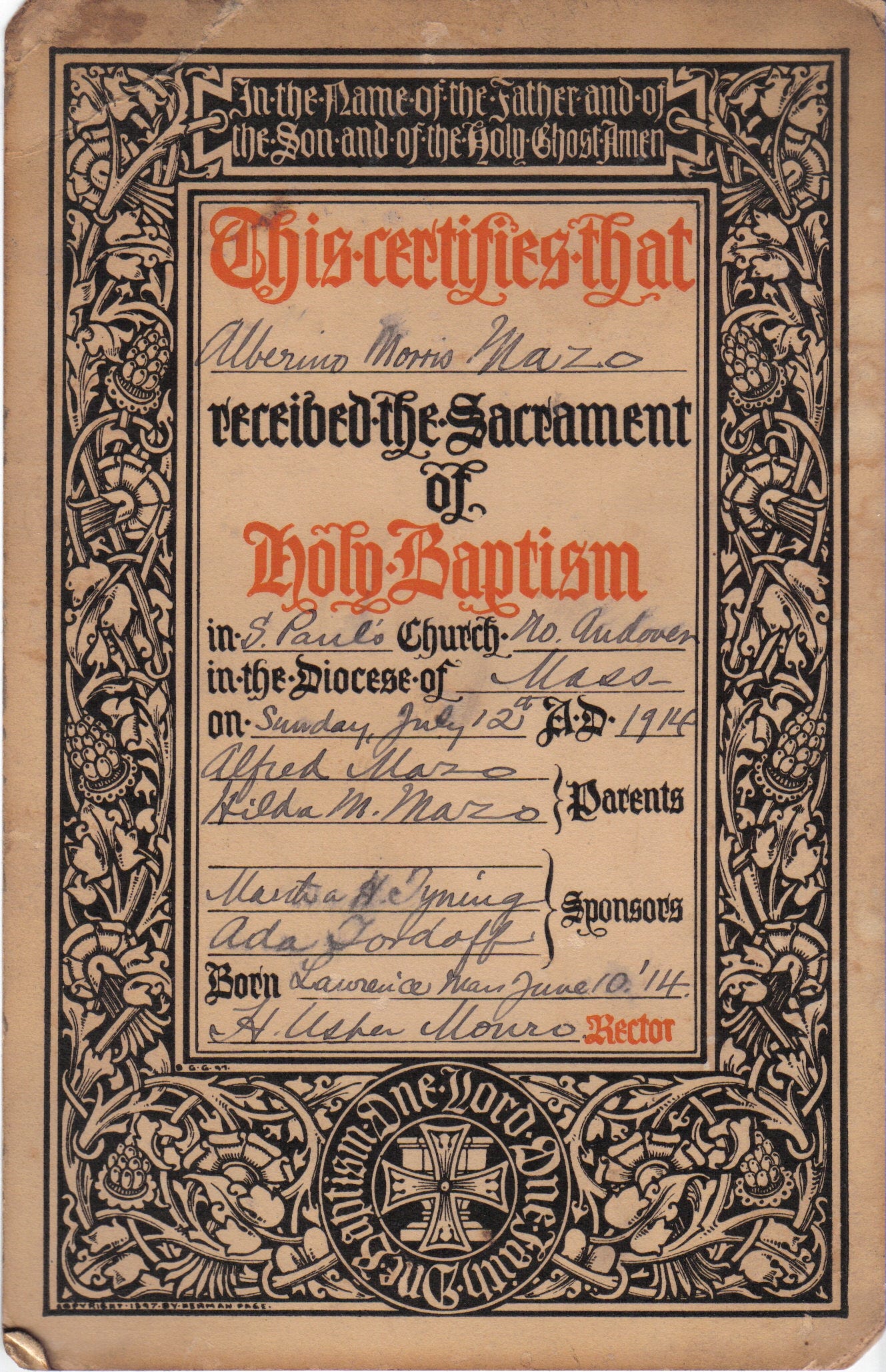

Albert Alberino Morris Mazo was born on June 10th, 1914, entering the world at a moment when industry, migration, and uncertainty defined daily life in the Merrimack Valley. The mills still governed the rhythm of the region, their whistles marking the hours, their labor shaping families and futures alike. He was born into a household formed by work and discipline, the son of parents whose lives were bound to machinery, faith, and endurance.

Shortly thereafter, on July 12th, he was baptized at St. Paul’s Church in North Andover, Massachusetts, formally received into the faith that had sustained the family across generations and across an ocean. The baptism placed him within an unbroken spiritual inheritance—one carried from the mountain fortresses of southern Italy into the brick parishes of New England, preserved not through ease, but through constancy.

The rite marked more than a religious obligation. It was an act of continuity. In a foreign land shaped by noise, speed, and change, the Church remained a fixed point—where names were recorded carefully, dates preserved, and families bound to something older than the mills that employed them. In holy water and prayer, Albert was joined to a lineage that measured time not only by years, but by duty and belief.

From the stone walls of Molise to the parish registers of New England, the family line was set down once more—name, date, place, and faith committed to record. What had once been preserved in memory and stone was now preserved in ink and sacrament, ensuring that amid movement and change, the essential things endured for those who would follow.

His baptismal record bore an iron cross, a simple and austere mark of the faith into which Albert Morris Mazo was received. It was not ornamental, but plain and enduring—fitting for a family shaped by labor, restraint, and continuity rather than display. The cross stood as a sign of sacrifice and permanence, echoing the same values that had carried the line from the stone strongholds of Molise to the mill towns of New England.

Set beside his name, date, and parish, the iron cross marked more than a ceremony. It testified to a faith meant to be carried quietly through work, loss, and time—fixed in record, yet lived out in daily obligation.

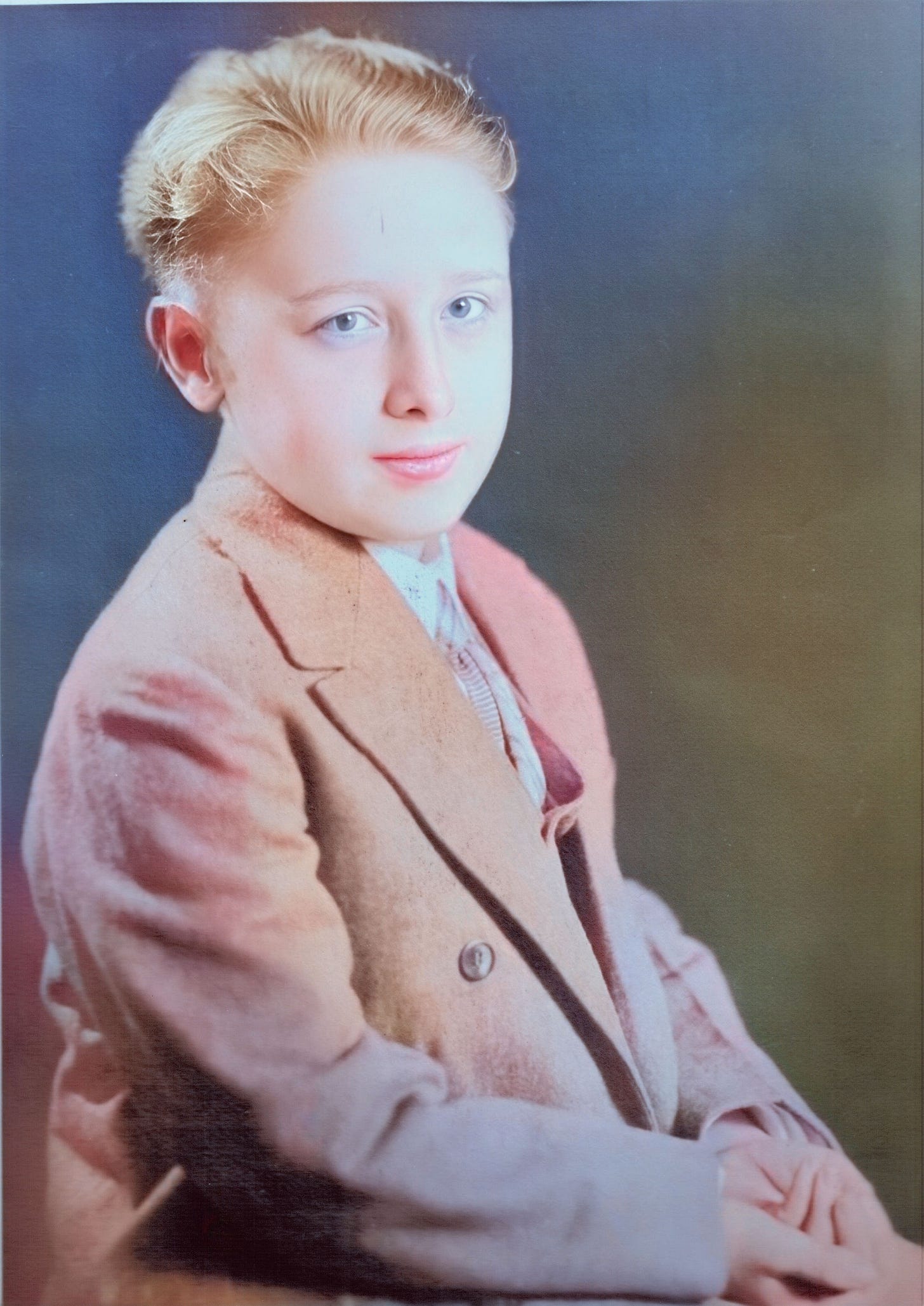

In this photograph below, Albert stands alone, small in stature yet deliberate in bearing. The uniform he wears is clearly too mature for him, its weight resting awkwardly on narrow shoulders, yet he does not slump beneath it. He stands upright, feet planted, hands still, eyes forward. There is no playfulness in the pose, no indulgence in childhood. Instead, there is attention—an early familiarity with expectation.

The setting is sparse, almost austere. Nothing distracts from the figure himself. The clothes suggest order, structure, and instruction rather than comfort, and his expression reflects the same. He appears already accustomed to being told where to stand and how to hold himself, already learning that posture and obedience mattered.

Looking at the image now, it is difficult not to see in it a kind of preparation. Not training, perhaps not destiny—but disposition. The quiet acceptance of discipline. The willingness to step into something larger than oneself and carry it properly, even when it does not yet fit.

What would come later was not visible to the photographer, nor perhaps to the child himself. Yet the qualities that would be required—steadiness, restraint, and the ability to endure responsibility without complaint—are already present. The photograph preserves a moment before the world asked more of him, while showing that, in some way, he had already begun to answer.

In the photograph, Albert stands dressed with care, his posture straight, his expression serious beyond his years. Pinned over his heart is a small badge, easily overlooked at first glance, yet placed with unmistakable intention. It is not decorative. It is devotional.

Such a mark was meant to be worn close to the heart, where belief was understood to reside—not as sentiment, but as discipline. Pinned there by a parent’s hand, it signified protection, obedience, and the expectation that faith was to be carried inwardly and borne outwardly through conduct. It was a quiet reminder that one belonged to something older and higher than oneself.

The pin does not announce itself. It does not command attention. Like the family itself, it speaks through restraint. In a childhood shaped by order, labor, and instruction, the badge over his heart served as a kind of early compass—fixing the center, teaching the child where he stood and what was required of him.

Seen now, the image captures more than a moment of youth. It records the early setting of values: faith placed at the center, duty worn close, and identity formed not by indulgence, but by inheritance. What would later be asked of Albert had not yet arrived, but the interior order needed to meet it had already been quietly fastened in place.

Soon, more Mazzoccos made their way to America. Word had traveled back across the Atlantic—not of ease, but of possibility sustained through work. Letters carried names, addresses, and instructions. Passage followed passage, each arrival tightening the bond between the old stone towns of Molise and the mill cities of New England.

What began as one man’s departure became a widening path. Brothers, cousins, and kin crossed in turn, carrying the same habits of labor, faith, and restraint. They settled near one another, worked the same floors, attended the same churches, and preserved in proximity what distance had threatened to loosen.

Thus the family did not dissolve in the New World; it reassembled. The name, though shortened and altered by records, endured in flesh and blood. What had once been held together by fortress walls was now held together by kinship, work, and shared memory—transplanted, but intact.

Some kept the name Mazzocco. Whether by circumstance, insistence, or simple fortune, it remained intact in certain records and households, carried forward as it had been for generations. In their keeping, the old name survived unchanged, anchoring memory to origin and preserving the sound and shape of the past.

Others bore altered forms, shortened by clerks or softened by use, yet the distinction was one of spelling rather than substance. Beneath the variations, the line remained the same—bound by blood, labor, and shared inheritance. The name might shift on paper, but its weight endured in practice and conduct.

Together, they formed a scattered continuity: some holding fast to the original, others adapting without surrender. In this way, the family persisted not as a single fixed mark, but as a living line—rooted in stone, tested by distance, and sustained through time.

In the photograph below, Albert is seated rather than standing, dressed carefully, his posture composed and deliberate. His clothing is formal for a child, arranged with care, suggesting not display but propriety. He looks toward the camera with calm attentiveness, with a slight smile he shows no signs of being uneasy, as if already accustomed to being observed and measured.

There is a stillness to him here that speaks of interior discipline. His hands rest where they have been placed. His expression is charming, warm, and unhurried. Nothing in the image suggests indulgence or excess. Instead, it reflects a childhood shaped by order, routine, and the expectation that one should carry oneself properly, even when young, while still maintaining happiness.

If the earlier photograph shows him learning how to stand within structure, this one shows him learning how to hold himself within it. Together, they reveal a boy formed early by restraint rather than impulse—one who listened, waited, and absorbed what was required of him.

Seen in retrospect, the image captures not innocence lost, but composure gained. It preserves the quiet formation of character before circumstance demanded more. What would later be asked of him was not yet visible, but the foundations—self-command, patience, and steadiness—are already unmistakably present.

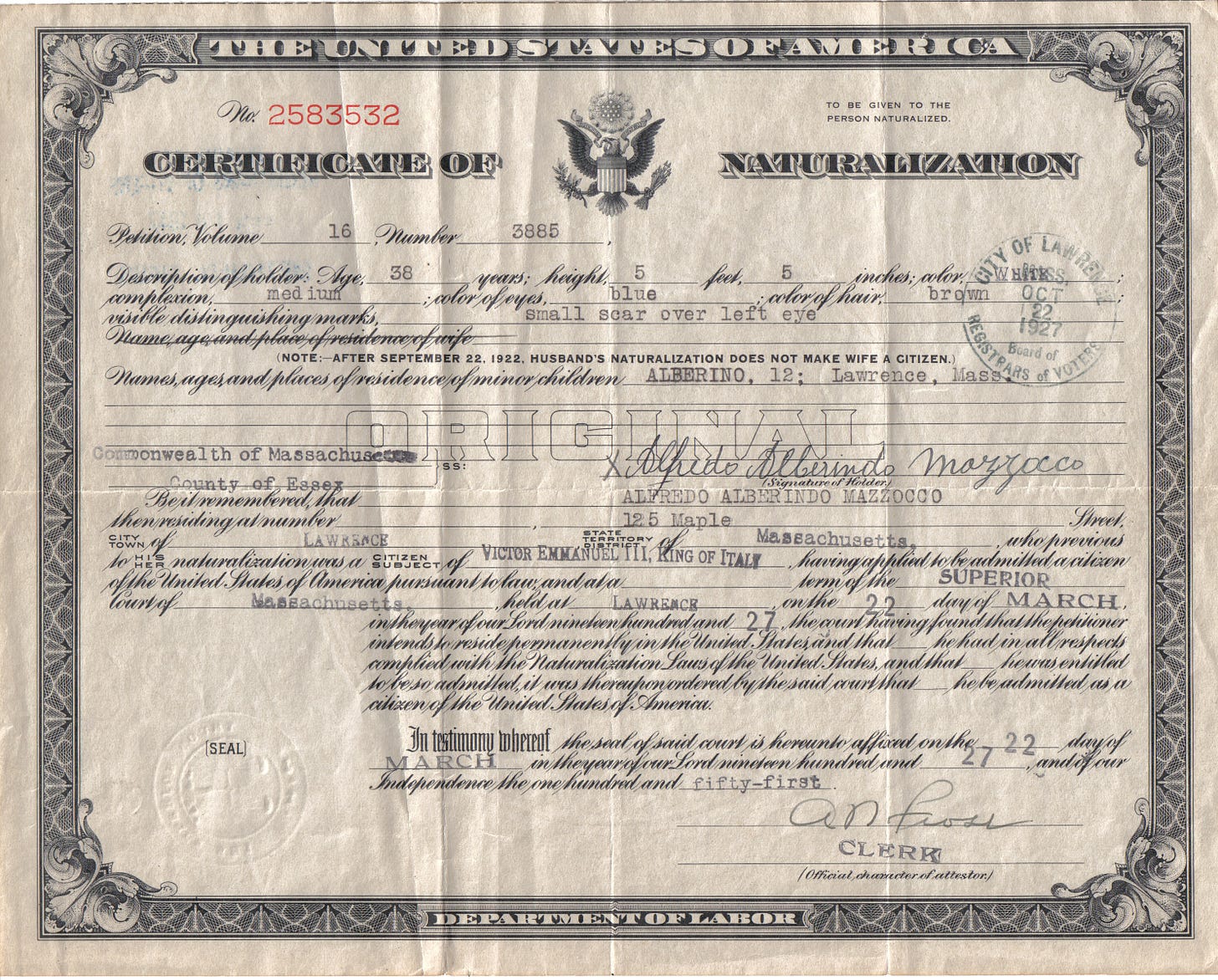

On March 22nd, 1927, after more than two decades of labor and settled life in Lawrence, Alfred became a naturalized citizen of the United States. The oath marked the final crossing of a journey that had begun in the stone fortress of Cerro al Volturno and passed through the mills of the Merrimack Valley.

Citizenship did not erase what came before it. It affirmed what had already been proven through years of work, responsibility, and family. By right of law, he now belonged to the country he had long served with his hands and his skill, securing a future for his children and fixing the family name firmly in American soil.

Ever the gifted mechanic, Alfred turned his attention once more to machines, this time not for industry nor necessity, but for his son. Drawing on years of experience and intuition, he began working on an airplane—assembling, adjusting, and refining it with the same care he had once given to mill machinery and engines. It was an act not of ambition, but of trust: faith in craft, in discipline, and in the judgment of the young man who would one day guide it.

What he built it for Albert to pilot carried its own meaning. What had been learned through labor was now offered forward, not as instruction alone, but as opportunity. The machine represented motion without confinement, elevation without escape—a continuation of the family’s long relationship with mechanics, now turned skyward.

In this way, the inheritance changed form but not substance. The same mind that once kept looms running now shaped wings and controls, preparing his son not merely to operate a machine, but to bear responsibility for it. What had crossed oceans and endured factories was now entrusted to air, carried forward by the next generation.

It was in 1938 that Hilda would pass. Her death marked a quiet but profound loss in the life of the family. She had shared the long hours of mill work, the discipline of labor, and the building of a home in a foreign land. As a spinner, a wife, and a mother, she had stood at the center of the household, her life woven into the same rhythm as the machines that once governed their days.

Her passing left a silence where there had once been steady motion. Yet what she had given endured—in her son, in the life they had built together, and in the resilience that defined the family. The work continued, the years moved forward, but the absence of her presence was lasting, carried quietly by those who remained.

In the years that followed, he would marry again. His second wife, Margaret Connors, became his companion through the later chapters of his life, sharing the burdens and quiet routines shaped by work, memory, and age.

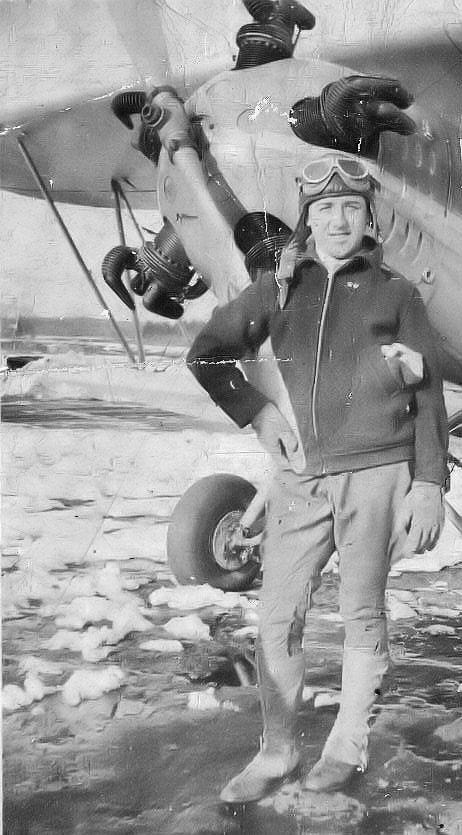

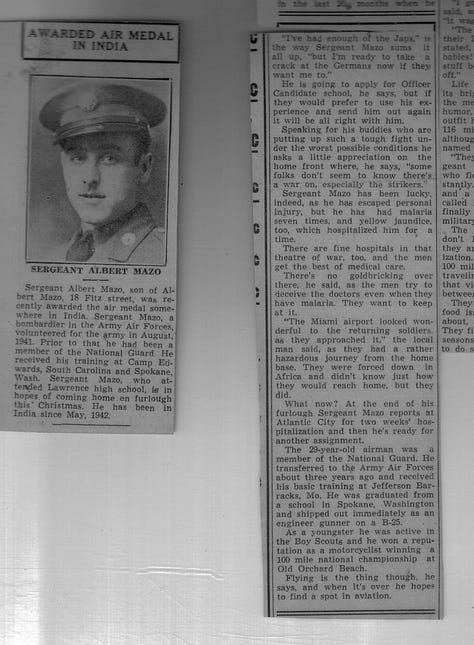

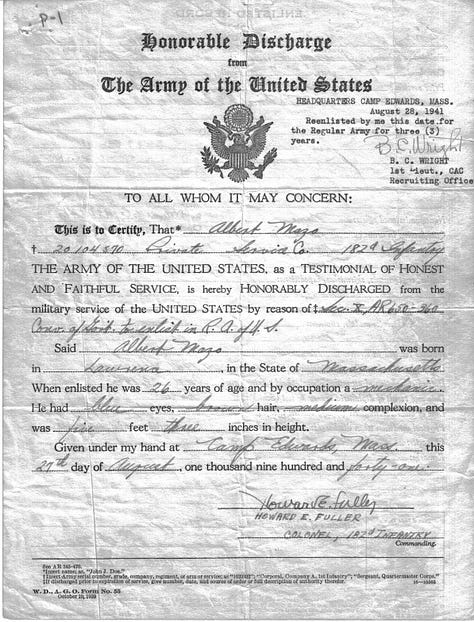

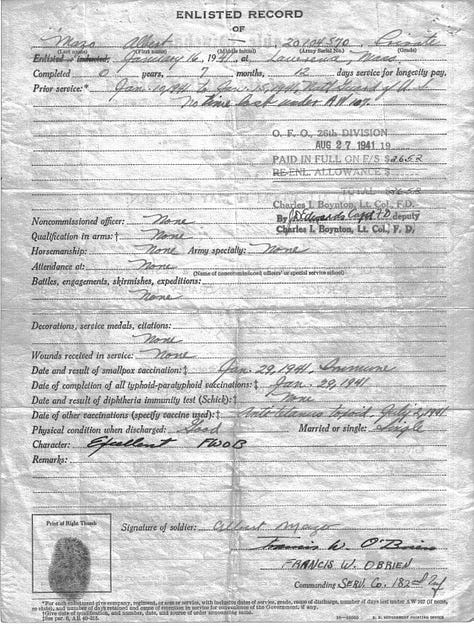

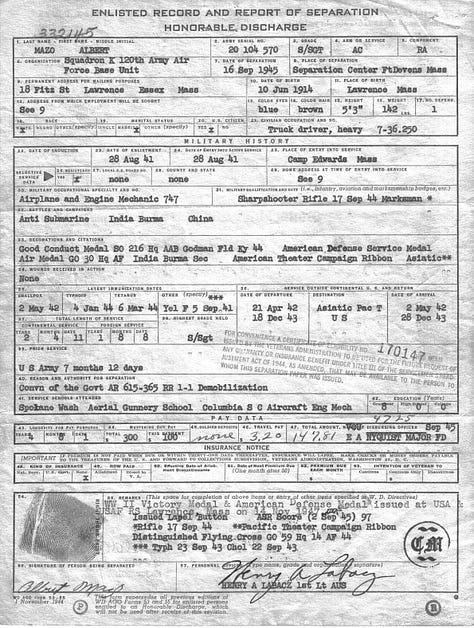

On August 28th, 1941, Albert joined the Army Air Forces. His decision came just weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor, at a moment when the future was uncertain and the demands of service were becoming unmistakable. It was a deliberate step, taken not in response to crisis, but out of conviction.

He joined to serve his country, understanding duty as something owed rather than demanded. At the same time, he sought to live out a long-held aspiration—to fly the greatest machines ever built. Flight, for him, was not romance but responsibility, requiring discipline, technical understanding, and calm under pressure.

Prepared by a childhood shaped by order, faith, and mechanics—and by a father whose hands understood machines as systems demanding respect—Albert entered the Army Air Forces ready to be tested. In the late summer of 1941, as the world moved toward war, he stepped forward, carrying with him an inheritance forged in stone, steel, and restraint.

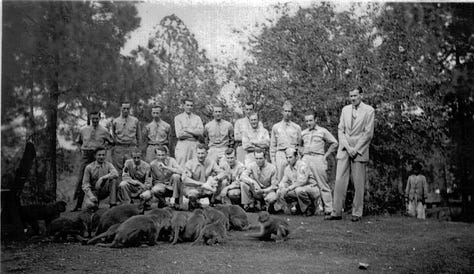

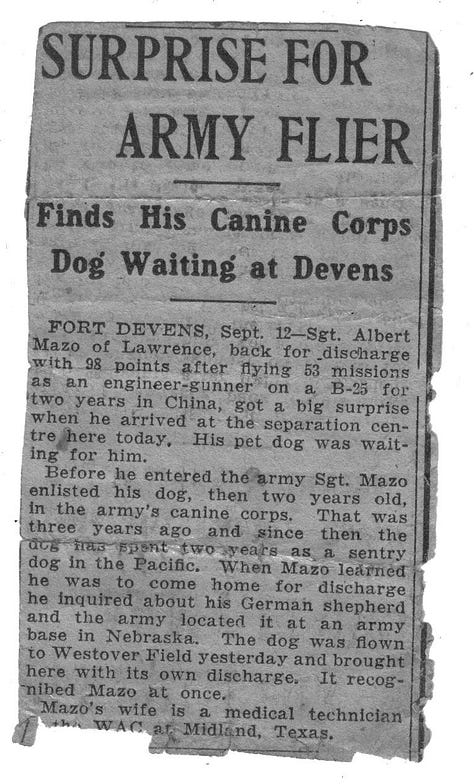

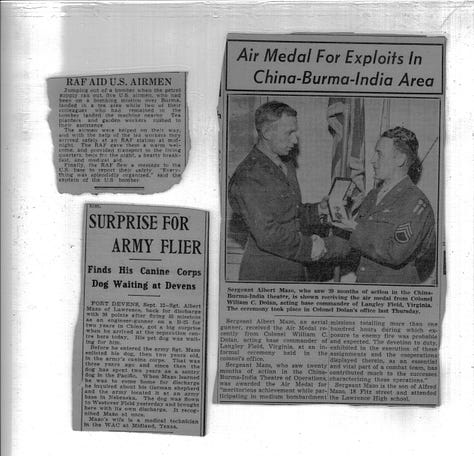

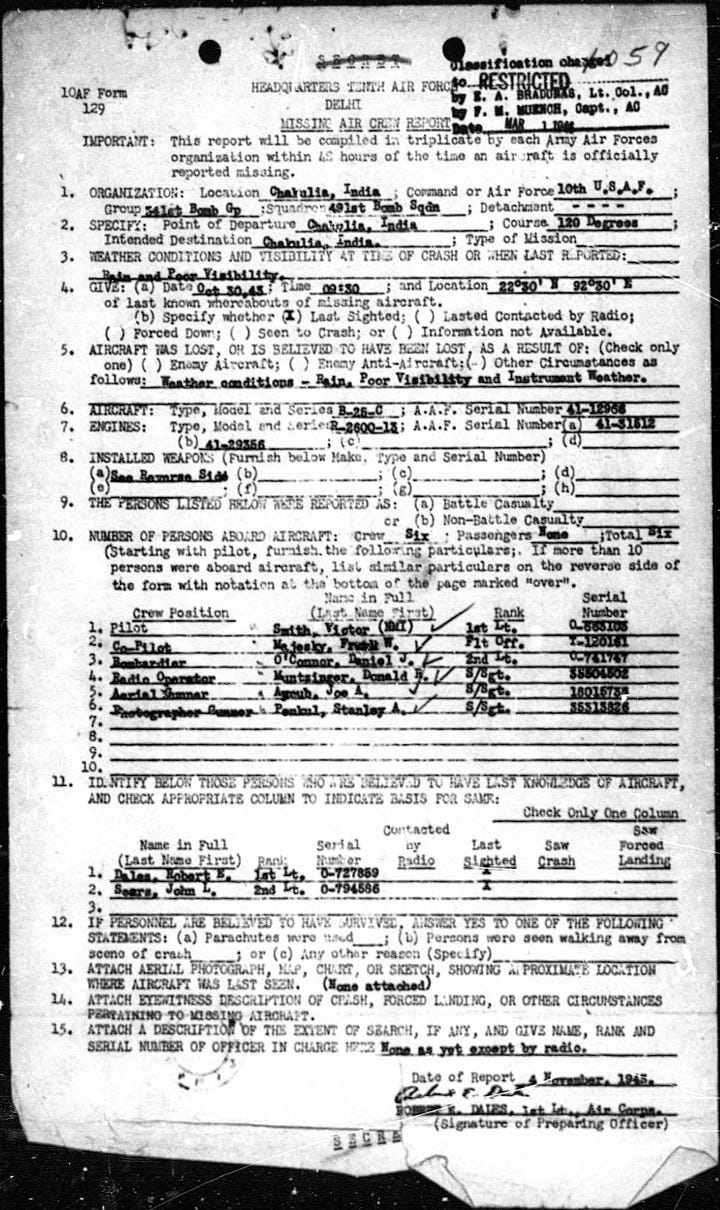

Assigned to the 14th Air Force, Albert became part of the 341st Bomber Group, a formation operating far from home and under demanding conditions. The work required precision, endurance, and trust—qualities shaped long before service, through discipline learned in childhood and through an understanding of machines as systems that rewarded respect and punished carelessness.

Within the group, flight was not spectacle but responsibility. Crews depended on one another completely, and machines were maintained and flown with an attention that allowed no excess and no error. What had once been learned in workshops and mechanical spaces now found its highest application in the air, where judgment, restraint, and skill were inseparable.

In this assignment, Albert’s path came into clear focus. The inheritance of craft passed down from his father, the composure formed early in life, and the quiet faith fixed at the center of the family all converged here. He served not as an individual apart, but as part of an ordered whole—one man within a unit, one crew within a group—carrying forward the same principles that had sustained the line across generations and continents.

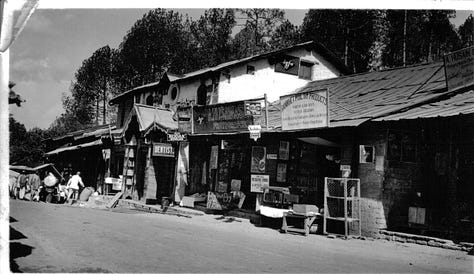

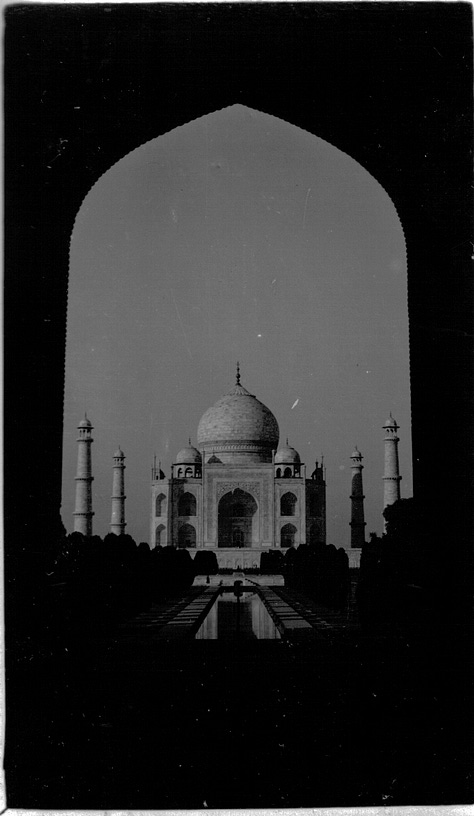

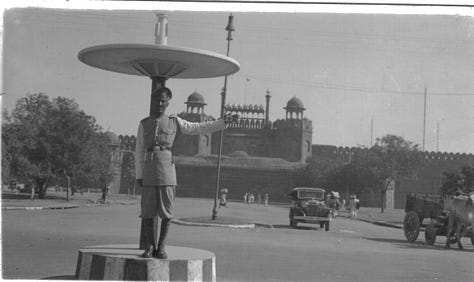

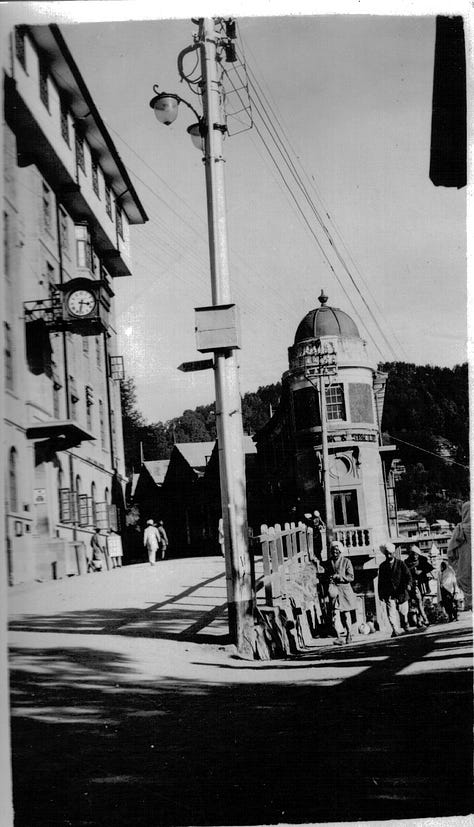

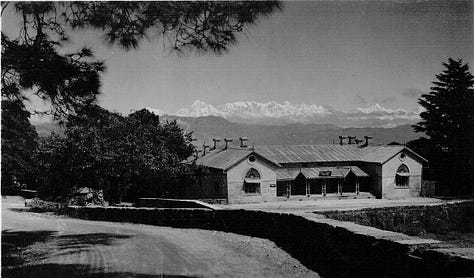

He was stationed in India, far from both the mills of New England and the stone towns of his family’s origin. From there, his service carried him into the skies over China, along routes defined by distance, weather, and necessity rather than borders familiar to him. The terrain below was foreign, vast, and unforgiving, demanding precision and calm from both crew and machine.

These flights were marked by endurance more than spectacle. Long hours, difficult conditions, and absolute reliance on navigation, mechanics, and judgment governed each mission. The aircraft were pushed to their limits, and the men who flew them were required to do the same—steadily, without excess, and without margin for error.

In this distant theater, Albert’s path reached its furthest point from the world that had formed him. Yet the inheritance traveled with him. The discipline learned in childhood, the respect for machinery passed down from his father, and the quiet faith fixed early at the center of his life all remained intact. Over unfamiliar land and beneath unfamiliar skies, he served with the same restraint and resolve that had carried his family across oceans and generations.

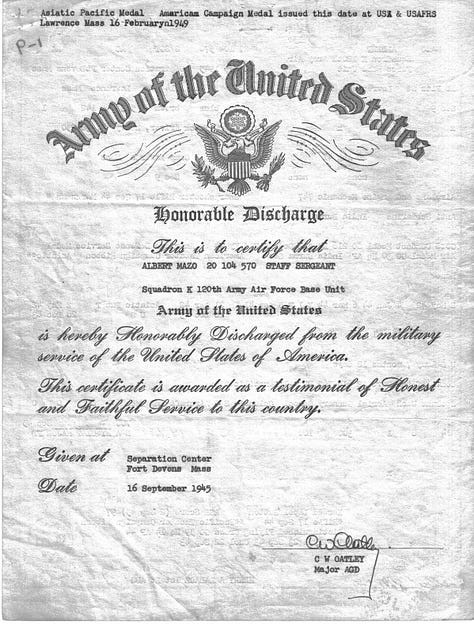

For my grandfather’s military prowess and heroism, he was awarded numerous medals, each marking service carried out with skill, endurance, and resolve. These honors were not granted for spectacle, but for sustained commitment—missions flown, responsibilities met, and judgment exercised under conditions that demanded the highest standard of conduct.

The medals testified to more than bravery alone. They reflected discipline learned early, respect for machinery and teamwork, and a willingness to accept risk without complaint. Each award stood as a formal recognition of what had already been proven in practice: that he could be relied upon when the margin for error was small and the cost of failure great.

Yet even in recognition, there was restraint. The decorations did not define him; they confirmed him. They served as quiet evidence of a duty fulfilled, adding to the record of a life shaped not by words, but by action—carried forward with the same steadiness that had marked his family across generations.

Despite the danger, Alfred supported his son. He understood the risks not as abstractions, but as realities measured in machinery, weather, and consequence. Having spent a lifetime respecting systems that could fail without warning, he knew precisely what flight demanded and what it could take.

Yet he did not discourage Albert. He had given him more than tools and knowledge; he had given him judgment. To withhold support would have been to deny the very inheritance he had passed down. What was built with care, he trusted to be used with care.

In this, Alfred’s faith was not naïve. It was earned. He had crossed an ocean, labored among machines, and shaped his son with discipline and restraint. If the skies now claimed that inheritance, he accepted it with the same resolve that had marked every other turning of the family’s course.

Support, in this sense, was not permission—it was confidence. And it bound father and son across distance, danger, and duty, as firmly as stone once bound their ancestors to the land.

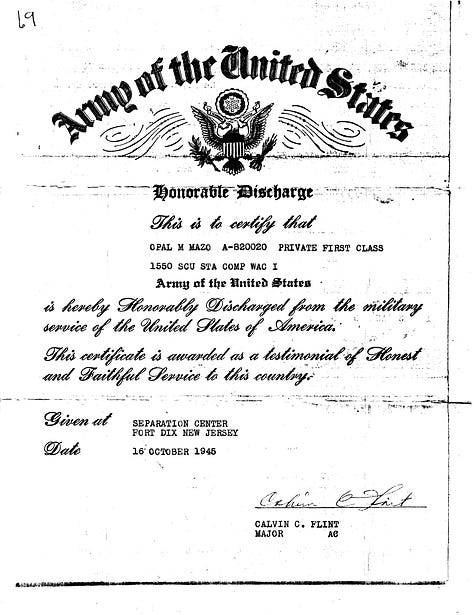

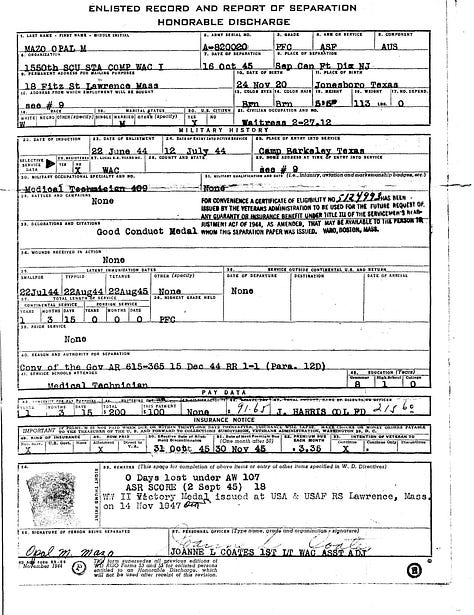

During Albert’s time in the military, he met Opal Melton, a medical technician, at a time when duty ordered daily life and the future remained uncertain. She was from Hamilton, Texas, far from the places that had shaped him, yet familiar in spirit. From the beginning, there was romance and love—not sudden or careless, but steady, deepening through shared purpose and mutual respect.

Their affection grew alongside their service. In the midst of assignments, separations, and the demands of war, they found in one another warmth, understanding, and certainty. What began as companionship became devotion. Their love was not an escape from responsibility, but something strengthened by it—a bond formed under pressure and sustained by choice.

They were married in Knox, Indiana, on March 16th, 1945, joining their lives while the conflict that had shaped their meeting was drawing to a close. The marriage was an act of faith in the future and in one another. In it, love took its rightful place beside duty, carrying forward the family line not only through endurance and service, but through affection freely given and steadfastly kept.

But as the war came to a close, there was still devastation, as there always will be. Albert’s closest friend, Joe, went missing while flying over India just a month after the war ended. It was a time when the world seemed like it was finally about to rebuild. But Joe’s death served as a reminder to my grandfather that war never leaves you.

After Opal and Albert were honorably discharged, they returned to Albert’s home, leaving behind the structures of military life and the long years of movement and uncertainty. Their service had concluded with distinction, and what had been demanded of them was fulfilled.

There, they began a life together—not suddenly, but deliberately. The habits shaped by duty remained: discipline, patience, and an understanding that stability is built through effort and care. They turned their attention to work, home, and the steady task of building a future.

Their return marked not an ending, but a transition. What had been tested in service was now carried into peace, where endurance and love could take lasting form, rooted at home and carried forward into the years ahead.

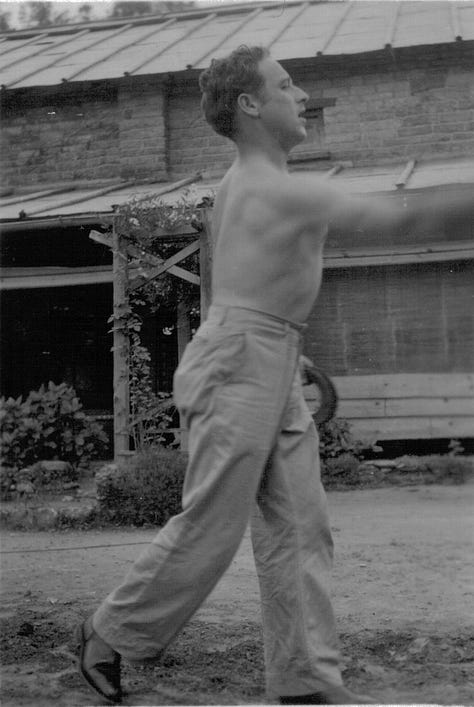

As civilian life resumed, Albert and Opal learned again how to move without orders. The rhythms of service gave way to choices once deferred, and the habits shaped by years of duty were slowly redirected toward peace. Work replaced assignments, home replaced quarters, and time—no longer measured by deployment—began to stretch forward again.

They adjusted together. What had carried them through uncertainty now helped them build stability: patience, humor, and an understanding that life after service required its own kind of discipline. There was room again for motion chosen freely, for moments taken not out of necessity, but for the simple fact of being able to take them.

One such moment came when they drove their jeep up Mount Washington. The climb was deliberate and unhurried, the road narrow and rising, the engine working steadily beneath them. It was not a test of endurance, but an affirmation of it. From the summit, the view opened wide and unobstructed—a landscape no longer bounded by schedules or borders.

In that ascent, there was quiet symbolism. The same machine once tied to service now carried them by choice. The same resolve that had sustained them through war now found expression in shared freedom. Together, they stood at the height of the mountain, not above the world, but at peace within it—beginning, at last, the life they had long prepared to live.

While Albert and Opal were fighting in the war, Alfred and his wife Margaret tilled the land at our family farm, living apart from the hustle and bustle of the city. The work was steady and physical, ordered by seasons rather than schedules. Mornings began early, shaped by weather and daylight, and the labor of the day ended only when the land allowed it.

There was dignity in the routine. The soil demanded patience and rewarded care, much as machines once had, though in a different register. What Alfred had learned through years of mechanical work now found expression in husbandry and maintenance, while Margaret brought order and constancy to the rhythms of the home.

Removed from the noise of industry, they built a quieter life—one grounded in effort, independence, and self-reliance. The farm did not erase the past; it absorbed it. In the turning of earth and the keeping of land, they found a measure of peace, and a place where endurance could finally be lived without urgency.

Though Alfred still worked diligently at the mill, the farm remained the center of their life beyond its walls. The long hours and mechanical discipline of his work carried over into the care of the land, shaping a routine that balanced industry with self-reliance. The mill provided stability; the farm provided grounding.

Each day was divided between obligation and intention. The noise and motion of machinery were answered by the quiet labor of soil and season. What was earned through wages was reinforced through work done by hand, ensuring that life was not wholly dependent on the rhythms of the city or the demands of industry.

In this way, Alfred bridged two worlds once more. He remained faithful to his responsibilities, yet rooted himself and Margaret in something enduring. The land did not replace the mill, but it tempered it—offering continuity, independence, and a measure of peace earned through steady, honest labor.

Thus, as the years advanced, Alfred’s life settled into a pattern shaped not by ambition, but by stewardship. Between the mill and the land, he sustained what he had built—work carried out faithfully, seasons honored, and obligations met without complaint. There was no retreat from responsibility, only a narrowing of focus toward what endured.

In this balance between industry and soil, the family line found a measure of stability earned rather than granted. What had once been forged in stone and later tested in steel was now preserved through patience and care. The rhythms of labor continued, quieter but no less demanding, anchoring the household in continuity rather than change.

It was here, in this ordered life between machine and earth, that the inheritance was secured for those who would follow—not as a relic of the past, but as a living example of endurance, restraint, and duty carried forward, one generation at a time.

Through these years, the line was sustained not by one figure alone, but by the quiet constancy of those bound to it. Hilda bore the early weight of labor and family in the mills, her life woven into the same discipline that shaped the household. Margaret carried Alfred through the later years, sharing both the burdens of work and the steadiness of rural life when the pace of industry began to slow. Opal stood beside Albert through war and its aftermath, anchoring love and stability where uncertainty had once prevailed. And Albert himself carried forward what had been given—faith, discipline, and responsibility—across continents, skies, and generations.

Together, they formed not a moment, but a continuity. Each held a place within the order of the family, each bearing a share of its obligations without display. What endured was not ambition, nor acclaim, but inheritance: labor honestly given, faith quietly kept, and duty accepted as a matter of course. In this way, the line did not merely persist—it remained whole, grounded in memory, sustained by example, and prepared to be carried forward once more.

This was beautifully written, sir. Thank you for the glimpse into the lives of those who came before. I look forward to the continuation of your work.